Coding Conventions and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Convention or Improvement

I was reading (and commenting on) a blog post by Jimmy Bogard at Los Techies yesterday. The basic premise was that, since Systems Hungarian Notation has basically been rejected by the developer community at large, it is interesting that we continue to pre-pend an “I” to interfaces in C#.

The post and some of the comments touched on the idea that while, yes, this is incongruous with eschewing systems Hungarian, we should continue to do it because it’s what other programmers expect and not following the convention makes your code less intuitive and readable to other C# developers. Jimmy says:

The train for picking different naming styles for interfaces and generic type parameter names left the station a long, long time ago. That ship has sailed. Picking a different naming convention that goes against years and years of prior art…

In the interest of full disclosure, I follow the naming convention and understand the point about readability, but it led me to consider a broader, more common theme that I’ve encountered in my programming career and life in general. At what point do we draw the line between doing something by convention because there is a benefit and mindlessly doing something by convention.

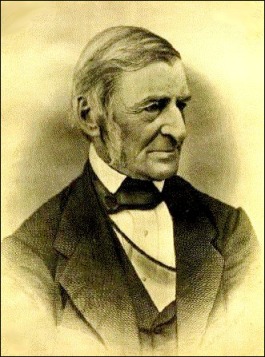

Ralph Waldo Emerson famously said, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” This is often misquoted as “Consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds,” which, in my opinion, frames my question here well. The accurate quote that includes “foolish” seems to suggest that following convention makes sense, so long as one continually justifies doing so, whereas the latter misses the subtlety and seems to advocate iconoclasm for its own sake, which, one might argue, is a foolish consistency in and of itself. We all know people that mindlessly hate everything that’s popular.

Lest I venture too far into philosophical considerations and away from the technical theme of this blog, I’ll offer this up in terms of the original subject for debate. Is the fact that a lot of programmers do something a valid reason to do it yourself, or is that justification an all purpose cudgel for beating people into following the status quo for its own sake? Is the convention argument a valid one of its own right?

Specifics

This is not the first incarnation in which I’ve seen this argument about convention. I’ve been asked to name method variables “foo” instead of “myFoo” because that’s a convention in a code base, and other people don’t prepend their variables with “my”. Ostensibly, it makes the code more readable if everyone follows the same naming scheme. This is one example in the case of countless examples I can think of where I’ve been asked to conform to a naming scheme, but it’s an interesting one. I have a convention of my own where class fields are pre-pended with underscores, method parameters are camel case, and method variables are pre-pended with “my”.

This results in code that looks as follows:

internal class Customer

{

private string _ssn;

internal string Ssn { get { return _ssn; } }

internal bool Equals(Customer customer)

{

var myOtherSocial = customer.Ssn;

return _ssn == myOtherSocial;

}

}

There is a method to my madness, vis-a-vis readability. When I look at code that I write, I can tell instantly whether a given variable is a class field, method parameter, or method variable. To me, this is clear and readable. What I was asked to do was rename “myOtherSocial” to “otherSocial” thus, in my frame of reference, losing the at-a-glance information as to what is a method parameter and what is a local variable. This promotes overall readability for the many while reducing readability for the few (i.e. me).

That’s an interesting tradeoff. One could easily make the Vulcan argument that better readability needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. But, one could also make the argument that the many should adapt to my convention, since it provides more information. Taking at face value that I’m right about my way being better (only for argument’s sake – I’m not arguing that there is a ‘right’ in a matter of personal readability and aesthetics) is the idea of convention — that a lot of people do it the other way — a valid argument against improvement?

Knowing When Conventions Can be Ignored

I don’t presume to know what the best naming scheme for local variable or interfaces is. In fact, I’d argue that it’s likely a matter of aesthetics and expectations. People who have a harder time mentally switching contexts are going to be more likely to dig in, and mile-a-minute, flighty thinkers will be more likely to get annoyed at such ‘pettiness’ and ‘foolish consistency’. Who’s right? Who knows – who cares.

Where the rubber meets the road is how consistency or lack thereof affects a development team as a whole. And, therein lies the subtlety of what to do, in my mind. If I am tasked with developing some library with a small, public facing API for my part in a team, it makes the most sense for me to write code in a style that makes me most productive. The fact that my code might be less readable to others will only be relevant at code reviews and in the API itself. The former is a one and done concern and the latter can be addressed by establishing “public” conventions to which I would then adhere. Worrying about some hypothetical maintenance programmer when deciding what to name and how to case my field variables is fruitless to a degree because that hypothetical person’s readability preferences are strictly unknowable.

On the other hand, if there is a much more open, collaborative paradigm where people are constantly modifying one another’s code, then establishing conventions probably makes a lot of sense, and following the conventions for their own sake would as well. The conventions might even suck, but they’ll be consistent, and probably save time. That’s because the larger issue with the consistency/convention argument is facilitating efficiency in communication — not finding The One Try Way To Do Things.

So, the “arbitrary convention” argument picks up a lot of steam as collaboration becomes more frequent and granular. I think in these situations, the “foolish consistency” becomes an asset to practical developers rather than a “hobgoblin of little minds.”

Be an Adapter Instead of an Evangelizer

All that said, the conventions and arguments still annoy me on some level. I can recognize the holistic wisdom in the approach while still being aggravated by being asked to do something because a bunch of other people are also doing it. It evokes images in my head of being forced to read “Us Weekly” because a lot of other people care how many times Matt Damon went to the gym this week. Or, more on subject, it evokes images of being asked to prepend “str” to all my string variables because other people think that (redundant in Visual Studio) information makes things more readable.

But, sometimes these things are unavoidable. One can go with it, or one can figure out a way to make all parties happy. I blogged previously about my solution to my own brushes with others’ conventions. My solution was a DXCore plugin that translated my conventions to a group’s, and vice-versa. I’m happy, the group is happy, and I learned stuff in the process.

So, I think the most important thing is to be an adapter. Read lots of code, and less will throw you off your game and cause you to clamor for conventions. Figure out ways to satisfy all parties, even if it means work-arounds or interesting solutions. Those give your brain some exercise anyway. Be open to both the convention argument and the argument for a new way of doing things. Go with the flow. The evangelizers will always be there, red faced, arguing that camel case is stupid and only pascal case makes sense. That’s inevitable. It’s not inevitable that you be one them.

(Image compliments of: http://geopolicraticus.wordpress.com/2009/01/28/short-term-thinking/ )