Does Github Enhance the Need for Code Review?

Editorial Note: I originally wrote this post for the SmartBear blog. You can check out the original here, at their site. Take a look around while you’re there and check out their products and other posts.

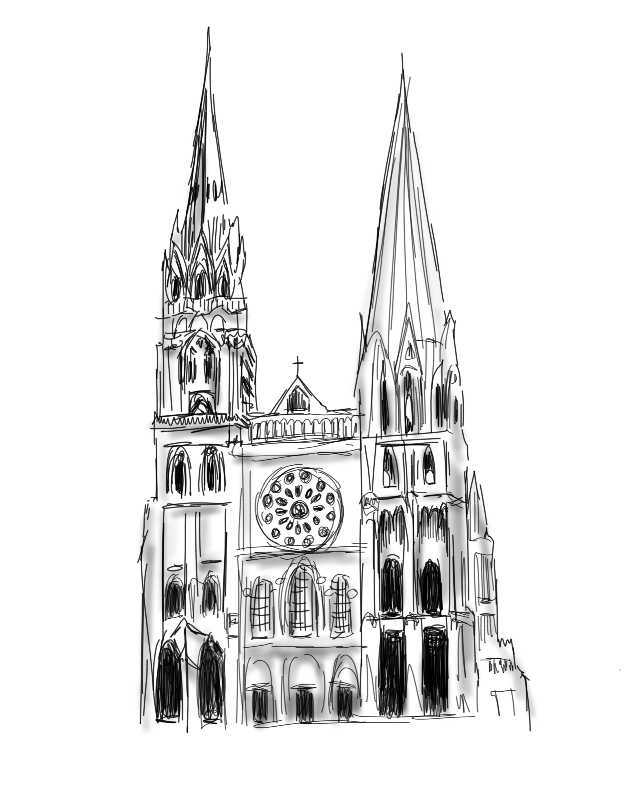

In 1999, a man named Eric S. Raymond published a book called, “The Cathedral and the Bazaar.” In this book, he introduced a pithy phrase, “given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow,” that he named Linus’ Law after Linux creator Linus Torvalds. Raymond was calling out a dichotomy that existed in the software world of the 1990s, and he was throwing his lot in with the heavy underdog at the time, the bazaar. That dichotomy still exists today, after a fashion, but Raymond and his bazaar are no longer underdogs. They are decisive victors, thanks in no small part to a website called Github. And the only people still duking it out in this battle are those who have yet to look up and realize that it’s over and they have lost.

Cathedrals and Bazaars in the 1990s

Raymond’s cathedral was heavily-planned, jealously-guarded, proprietary software. In the 1990s, this was virtually synonymous with Microsoft, but certainly included large software companies, relational database vendors, shrink-wrap software makers, and just about anyone doing it for profit. There was a centrally created architecture and it was executed in top down fashion by all of the developer cogs in the for-profit machine. The software would ship maybe every year, and in the run up to that time, the comparably few developers with access to the source code would hunt down as many bugs as they could ahead of shipping. Users would then find the rest, and they’d wait until the next yearly release to see fixes (or, maybe, they’d see a patch after some months). The name, “cathedral” refers to the irreducible nature of a medieval cathedral — everything is intricately crafted in all or nothing fashion before the public is admitted.

The bazaar, on the other hand, was open source software, represented largely at the time by Linux and Apache. The source code for these projects was, obviously, free to all to look at and modify over the nascent internet. Releases there happened frequently and the work was crowd-sourced as much as possible. When bugs were found following a release, the users could and did hunt them down, fix them, and push the fix back to the main branch of the source code very quickly. The cycle time between discovery and correction was much, much smaller. This model was called the bazaar because of the comparably bustling, freewheeling nature of the cooperation; it resembled a loud, spontaneously organized marketplace that was surprisingly effective for regulating commerce.