Editorial Note: I originally wrote this post for the SubMain blog. You can check out the original here, at their site. While you’re there, take a look at CodeIt.Right and its automated code review capabilities.

As a teenager, I remember having a passing interest in hacking. Perhaps this came from watching the movie Sneakers. Whatever the origin, the fancy passed quickly because I prefer building stuff to breaking other people’s stuff. Therefore, what I know about hacking pretty much stops at understanding terminology and high level concepts.

Consider the term “zero day exploit,” for instance. While I understand what this means, I have never once, in my life, sat on discovery of a software vulnerability for the purpose of using it somehow. Usually when I discover a bug, I’m trying to deposit a check or something, and I care only about the inconvenience. But I still understand the term.

“Zero day” refers to the amount of time the software vendor has to prepare for the vulnerability. You see, the clever hacker gives no warning about the vulnerability before using it. (This seems like common sense, though perhaps hackers with more derring do like to give them half a day to watch them scramble to release something before the hack takes effect.) The time between announcement and reality is zero.

Increased Deployment Cadence

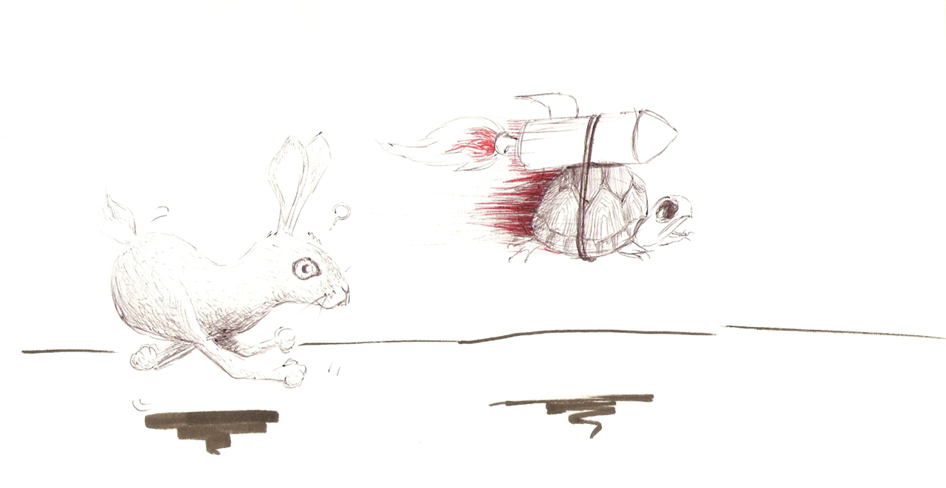

Let’s co-opt the term “zero day” for a different purpose. Imagine that we now use it to refer to software deployments. By “zero day deployment,” we thus mean “software deployed without any prior announcement.”

But why would anyone do this? Don’t you miss out on some great marketing opportunities? And, more importantly, can you even release software this quickly? Understanding comes from realizing that software deployment is undergoing a radical shift.

To understand this think about software release cadences 20 years ago. In the 90s, Internet Explorer won the first browser war because it managed to beat Netscape’s plodding release of going 3 years between releases. With major software products, release cadences of a year or two dominated the landscape back then.

But that timeline has shrunk steadily. For a highly visible example, consider Visual Studio. In 2002, 2005, 2008, Microsoft released versions corresponding to those years. Then it started to shrink with 2010, 2012, and 2013. Now, the years no longer mark releases, per se, with Microsoft actually releasing major updates on a quarterly basis.

Zero Day Deployments

As much as going from “every 3 years” to “every 3 months” impresses, websites and SaaS vendors have shrunk it to “every day.” Consider Facebook’s deployment cadence. They roll minor updates every business day and major ones every week.

With this cadence, we truly reach zero day deployment. You never hear Facebook announcing major upcoming releases. In fact, you never hear Facebook announcing releases, period. The first the world sees of a given Facebook release is when the release actually happens. Truly, this means zero day releases.

Oh, don’t get me wrong. Rumors of upcoming features and capabilities circulate, and Facebook certainly has a robust marketing department. But Facebook and companies with similar deployment approaches have impressively made deployments a non-event. And others are looking to follow suit, perhaps yours included.

Read More